When Chatsworth House reopened its doors to the public in May 2021, it also welcomed some other returning visitors: Falconry and Swan and Otter Hunt, two from the set of four tapestries known today as the Devonshire Hunting Tapestries.

Impressive in scale and rich in detail, these fifteenth-century Flemish tapestries show medieval men and women engaging in hunting and falconry in imaginary forest scenes. The tapestries were in the Cavendish family’s possession, possibly for more than 400 years, before being transferred to public ownership in 1957 in lieu of inheritance tax; they’ve since been in the care of the V&A.

Late 2021, they were loaned to Chatsworth and displayed in the Sculpture Gallery right at the end of the visitor journey through the house – ‘grand finale’ is an understatement – but they’ve not always looked so impressive. Quite the opposite, actually: just over a century ago, the tapestries looked anything but. In this two-part blog, we’ll delve into the past lives of the Devonshire Hunting Tapestries and trace some of the people who’ve cared for them.

The Devonshire Hunting Tapestries were on display in the Sculpture Gallery at the end of 2021. Loan in Partnership with the V&A. © Chatsworth House Trust. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, 2021.

Twenty miles east of Chatsworth sits another grand house, Hardwick Hall, which – like the Elizabethan house that once stood at Chatsworth – was built by Bess of Hardwick.

Known locally as ‘Hardwick Hall, more glass than wall’, Hardwick was for many years a favoured summer retreat for the family. The winter months, however, were a different story: those beautiful windows offered nothing in the way of insulation. In the winter of 1845, the 6th Duke of Devonshire recorded in his diary that ‘a vain attempt was made to pass some evenings in the Long Gallery, [but] although surrounded by screens and sheltered by red baize curtains, the cold frosty weather got the better of us.’

This may explain why, during a summer visit some fifty years later, the Duke’s great-niece Lady Louisa Egerton made a curious discovery in the Long Gallery. She recalled that ‘in the two recesses, folded and refolded was a store of tapestry which has proved to be of the greatest interest’ – none other than the Devonshire Hunting Tapestries, cut to pieces and used as draught excluders.

Woven with quality wool threads, these tapestries were functional objects as well as decorative ones; evidently, then, they’d been stuffed into the wall niches to insulate the vast stone hall.

Chatsworth Librarian Arthur Strong and Rev Charles Kerry, a clergyman and local historian, pushed for the tapestries to be reconstructed and properly cared for – Kerry declared them ‘unquestionably, the finest and most valuable tapestry in Hardwick and perhaps in the [UK],’ noting their piecemeal state with much regret. Strong, meanwhile, wrote to the V&A to ask for their assistance with reconstructing and cleaning the tapestries.

Work to reassemble the Hunting Tapestries began in December 1900. Lady Louisa Egerton, always eager to throw herself into anything involving conservation, was on hand:

I cannot describe the interest it was to see piece after piece taken down and laid on the floor of the gallery – sometimes we found that the legs of the same man were in different recesses! But this delightful puzzle eventually resolved itself into four large pieces…

The reconstruction was coordinated by the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A) and undertaken by the Decorative Needlework Society, under the watchful eye of one Miss Elizabeth Gemmell.

Born in Glasgow in 1840, Elizabeth Gemmell came from a family of creative women: her younger sister Mary was a landscape painter and an embroiderer (the sisters worked side by side in this respect), while her older sister Marion was a portrait painter and a contemporary of William Holman Hunt.

Elizabeth was a skilled embroiderer, and she was for many years workroom mistress at the Royal School of Needlework; the School was closely affiliated with the V&A, moving in next door when it expanded its operations in 1903.

At the RSN’s first home in nearby Sloane Street, Elizabeth and her contemporaries founded the Decorative Needlework Society. The Society’s chief aims were to undertake textile restoration and repair and, according to The Sketch, to provide ‘artistic and congenial employment’ for middle-class women.

Both the Royal School and the Decorative Needlework Society rode on the crest of a decorative embroidery revival, initiated by Arts & Crafts pioneers like Walter Crane and May Morris (often overshadowed by her more famous father). Elizabeth and her sisters would have moved amongst the artistic luminaries of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with the V&A as the nexus between this thriving cultural circuit and the altogether more sedate world of the country house.

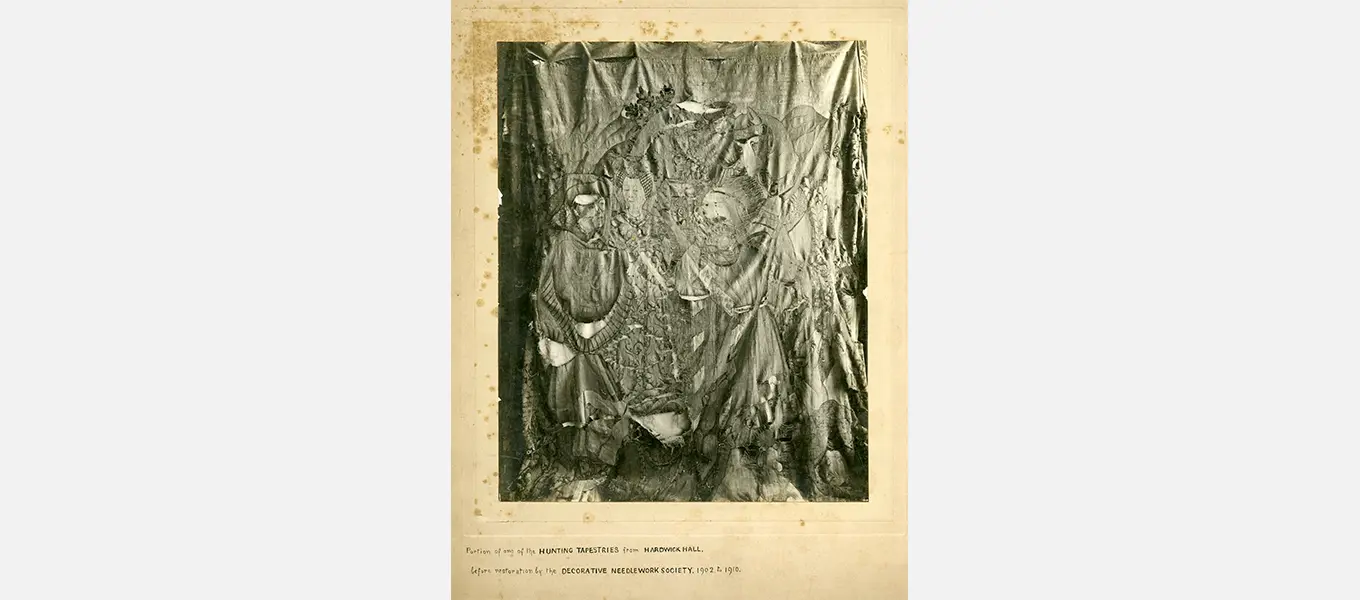

A reconstructed section of the Swan and Otter Hunt tapestry before the tapestry’s restoration by the Decorative Needlework Society (c.1901). Credit: Devonshire Collection Archives.

Many hands make light work, or so the saying goes – still, when Elizabeth Gemmell and her team began piecing together the Devonshire Hunting Tapestries, they had a mammoth task ahead of them. In February 1902, fourteen months in, the Society completed the restoration of the first tapestry, Swan and Otter Hunt. The result of their hard work was briefly exhibited at the V&A before returning to Hardwick. Describing this exhibition and the tapestry’s ‘phoenix-like’ transformation, the Pall Mall Gazette praised the women’s work:

It is impossible for anyone, not having seen the mutilated state in which [they were rediscovered], to realise the enormous amount of labour for the proper readjustment of the various strips and bits.

Even with a team of eight women working full-time, it took the best part of a decade to reconstruct and restore the whole set. By 1905 two of the restored tapestries had made their way to Chatsworth, where they were displayed in the Sculpture Gallery for many years.

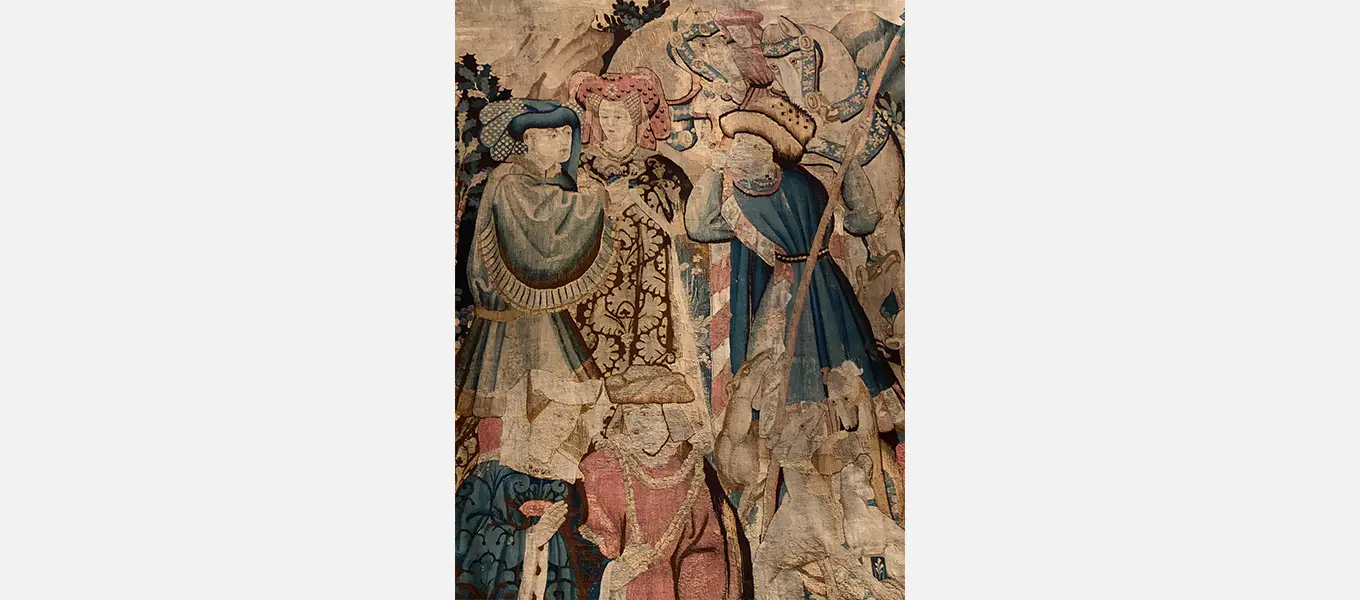

The same section of the Swan and Otter Hunt, restored (2021).© Chatsworth House Trust. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, 2021

The 6th Duke’s repurposing of these works of art might seem like sacrilege to modern eyes, but ironically enough, his ‘resourcefulness’ is the reason that the Hunting Tapestries have survived. Many other examples were lost or destroyed long before these tapestries’ rediscovery in the late nineteenth century, and were it not for the renaissance of decorative tapestry around this time, perhaps they too wouldn’t have been so painstakingly restored by Elizabeth Gemmell and co.

In our next blog, we’ll return to the Devonshire Hunting Tapestries several decades down the line, at a time when their threads – and their future – didn’t look so bright.