Charlotte Newcombe is a PhD researcher at the University of York, who has recently been working with our Archive and Library team.

Between January and March, I worked on a project with Chatsworth’s incredible collection of incunables (books printed pre-1501). While completing the project I became curious about some of the other books in Chatsworth’s collection.

Specifically, I wondered if Chatsworth had any books by Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle (1623–1673), a prolific writer and natural philosopher, and one of the women I am researching for my PhD.

The Cavendish Family and Thomas Hobbes

Margaret Cavendish’s husband, William Cavendish, the 1st Duke of Newcastle (1593–1676), was one of Bess of Hardwick’s grandsons, and therefore a cousin of the 2nd and 3rd Earls of Devonshire, both (confusingly) also called William Cavendish.

Thomas Hobbes was the tutor and companion to the 2nd and 3rd Earls of Devonshire, and responsible for Hardwick’s growing library. He was also associated with the ‘Newcastle Circle’, an intellectual group centred around the Duke of Newcastle and his brother, Charles. Margaret even reports seeing Hobbes at dinner with her husband, although denies having spoken to him herself.

Margaret Cavendish published across a variety of genres including poetry, letters, plays, philosophical tracts, and even an early work of science fiction. She distributed her books widely, including (most audaciously) to the then existing colleges at Oxford and Cambridge universities and to other philosophers, such as Hobbes.

In a 1661/62 letter to Margaret, Hobbes thanks her for sending him one of her books (likely the 1662 edition of her ‘Playes’), commenting that he’d already read much of it “in that Book which my Lord of Devonshire has”.

With all of this in mind, it seemed possible that Cavendish had sent copies of her books to her husband’s cousins at Hardwick and Chatsworth.

The Seventeenth-Century Library

The seventeenth-century library catalogues for Hardwick Hall include a large portion of Cavendish’s many printed books.

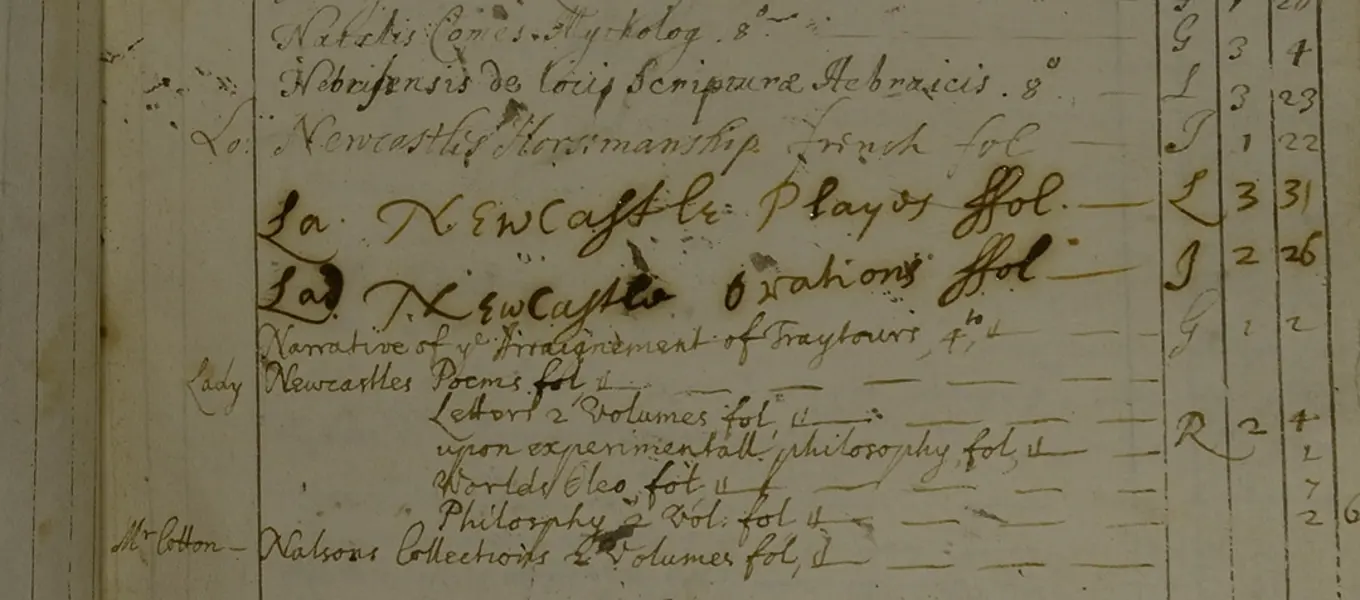

Image from a catalogue of Hardwick Hall’s library composed by James Wheldon

Notably, the catalogue composed in c.1657 by James Wheldon and possibly overseen by Hobbes lists 9 volumes written by “Lady Newcastle”.

Most, if not all, of the listed books were printed after 1657 and so were added to the catalogue after its initial composition, likely in two groups given the gap between the first two listed and the others, as well as differences in the handwriting.

Both Cavendish’s “Playes” and “Orations” were first printed in 1662, so it seems likely that these two books were added to the catalogue together at around this time.

Could the “Playes” be the Earl of Devonshire’s copy that Hobbes claims to have read in his letter?

Many of the other books listed are harder to identify. Cavendish frequently reprinted her books in often heavily revised editions. For example, her poems were printed in 1653, 1664, and 1668 and her philosophical treatise in 1653, 1655, 1663, and 1668. From the information in the catalogue (“Poems” and “Philosophy, 2 Vol:”) it’s difficult to say exactly which the listed books are.

It's possible to speculate about others. “Letters, 2 Volumes” are likely ‘Philosophical Letters’ and ‘Sociable Letters’, both printed in 1664, and “Worlds Oleo” is the ‘Worlds Olio’, first printed in 1655 and then reprinted in 1671. Finally, “upon experimentall philosophy” refers to Cavendish’s ‘Observations upon Experimental Philosophy’ that was printed with her proto-science fiction ‘The Blazing World’ in both 1666 and 1668.

In both ‘Philosophical Letters’ and ‘The Blazing World’ Cavendish critiques Hobbes’s philosophy. Given his presence at Hardwick and Chatsworth, could Hobbes have read Cavendish’s criticisms of his work?

The Current Library

Given the extent of the seventeenth-century collection, I was interested to see if Chatsworth’s library still held any Cavendish books. A search of the catalogue revealed three. A 1655 edition of ‘Philosophical and Physical Opinions’ could be one of the volumes of “Philosophy” listed in the c.1657 catalogue but could also be a later acquisition, while an edition of her biography of her husband is certainly a later addition to the library.

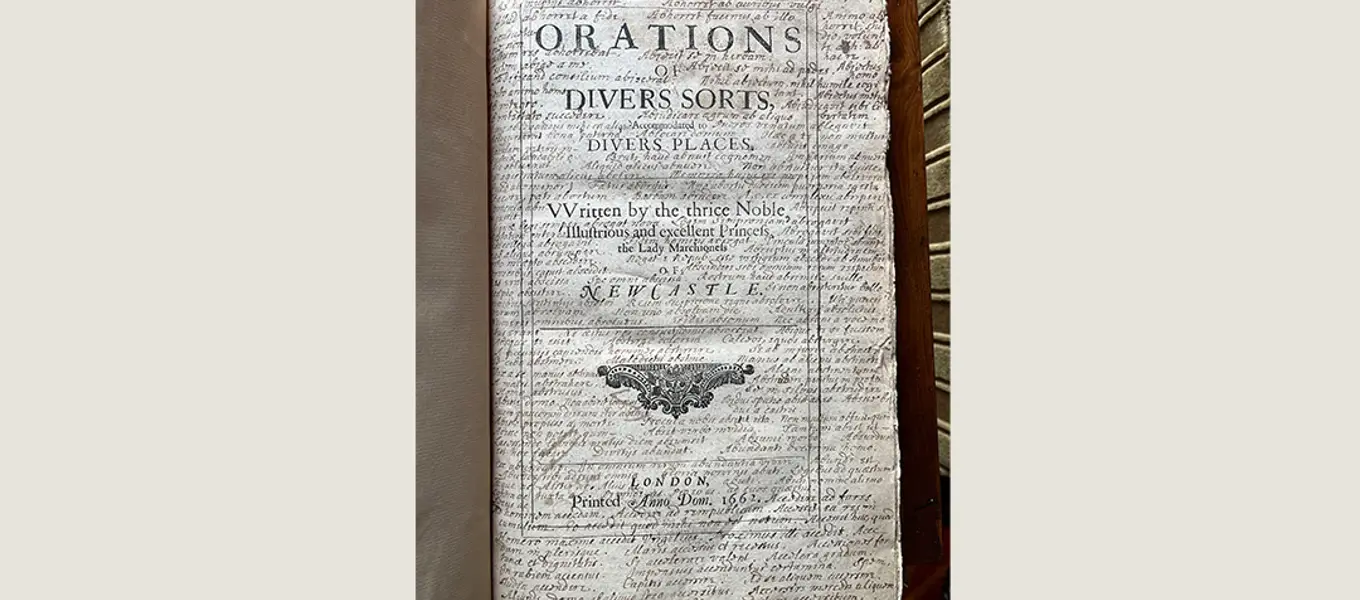

The final book currently in the library is a 1662 edition of Cavendish’s ‘Orations’. When I saw this book in the library I was surprised and excited to see that it was covered in annotations.

Clement Ellis’s Copy of ‘Orations’

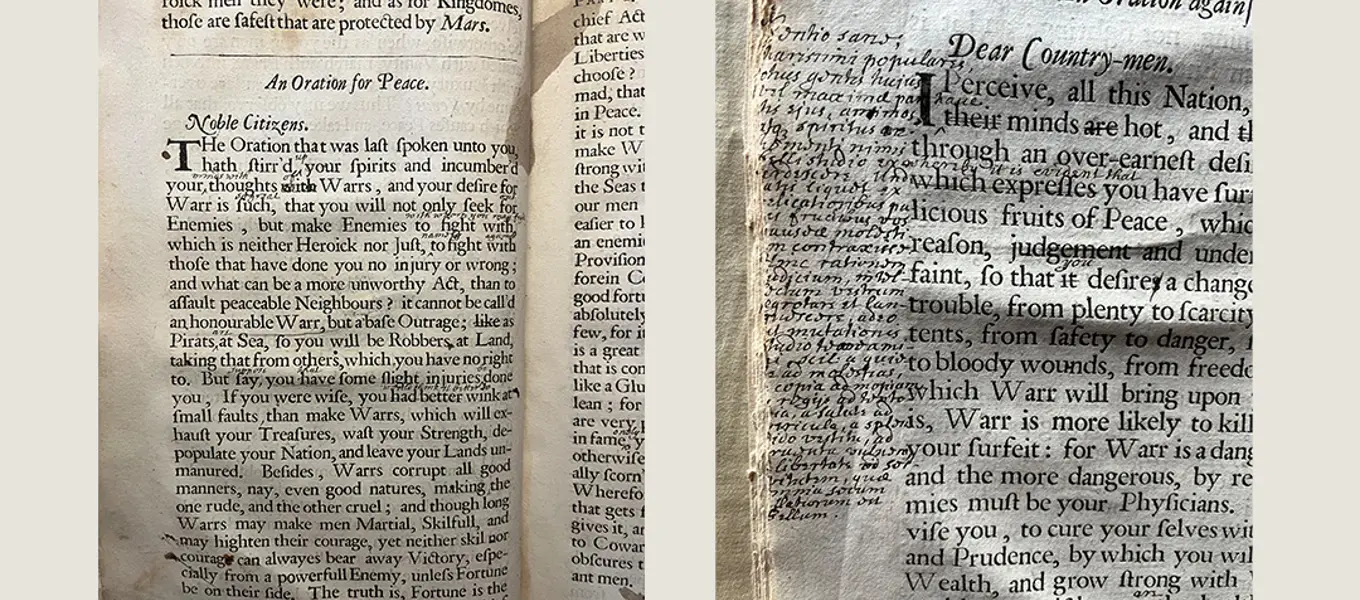

Cavendish’s ‘Orations’ is a series of fictional speeches on various topics, from war to marriage, from taxes to the plague.

Chatsworth’s copy of ‘Orations’ bares numerous ownership marks, and its provenance can be traced outside the Devonshire family until at least the beginning of the eighteenth century, so it’s highly unlikely to be the copy listed in the c.1657 catalogue of Hardwick’s library.

Nonetheless, the book does have a fascinating direct connection to Margaret Cavendish: “Clement Elis” is written into the book several times. Clement Ellis (1633–1700) was appointed as William and Margaret Cavendish’s domestic chaplain at their Welbeck estate in around 1660 or 1661.

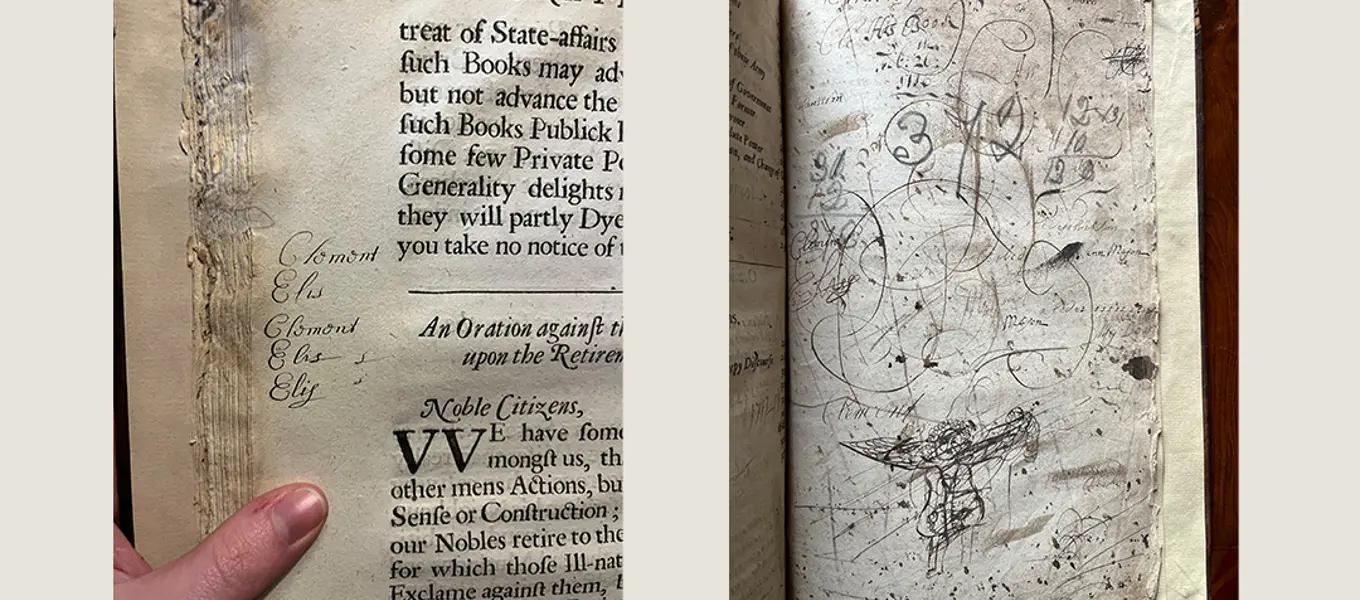

Images from Margaret Cavendish’s ‘Orations’, 1662. From left to right, p.66 showing “Clement Elis” written in the margin; then a back page, heavily written on. Clement Ellis’s name is visible on the mid-left, but “Clement” is also written above what appears to be a drawing of an angel.

Clement Ellis seems to have enjoyed a close relationship with the Newcastle household. A biography published after his death claims that family members would “suffer themselves to be reproved by the Chaplain”. He also contributed a poem to the commemorative volume published upon Margaret’s death. In it he praises her books highly as the “Muses Common-wealth” and claims that “her very Dreams outvie / All our grave Lectures of Philosophy”. One nineteenth-century genealogist reports that Margaret Cavendish was the godmother of Ellis’s only daughter, also Margaret, born in 1665.

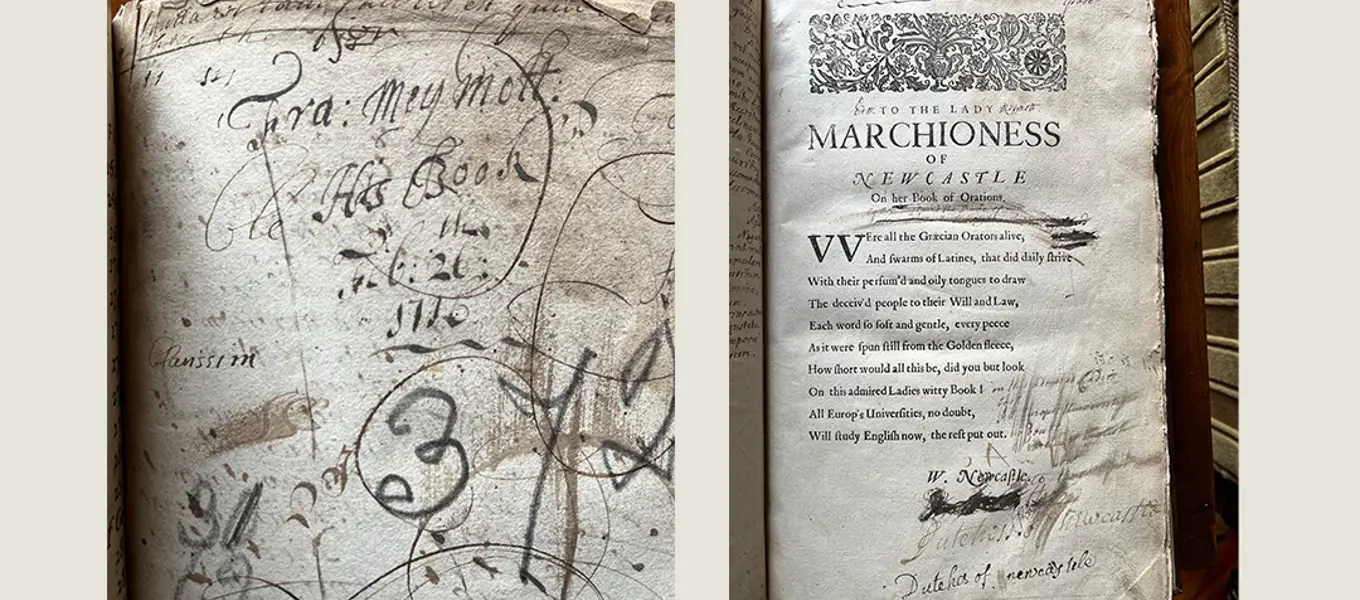

Margaret Ellis (1665–1714) went on to marry Joseph Meymott, a connection that perhaps explains two of the other names in Chatsworth’s copy of ‘Orations’. “Fra: Meymott. His Book Feb 26th 1716” is written on an originally blank back page, with “Edm: Meymott” featuring on one of the opening pages.

Images from Margaret Cavendish’s ‘Orations’, 1662. From left to right, Francis Meymott’s signature; then an unpaginated opening page featuring Edmund Meymott’s name visible on either side of the title “To the Lady”.

Margaret and Joseph Meymott appear not to have had a son called either Francis or Edmund, but Joseph did have a brother by that name who was born in 1664 and died in 1722. This Francis Meymott did have a son called Reverend Edmund Meymott (1694–1770). However, Edmund seems to have been a very common Meymott family name: Joseph and Francis’s father was also called Edmund, they had another brother called Edmund, and Rev. Edmund Meymott also had a son called Edmund.

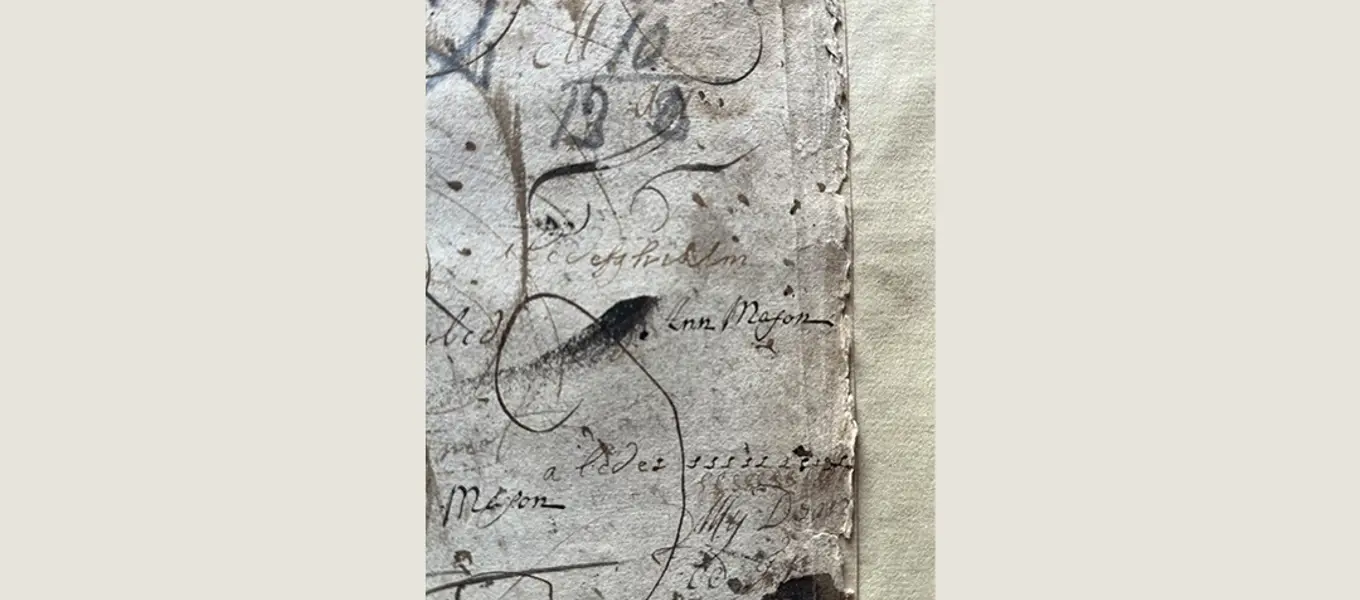

The final name inscribed into the book also appears on its final messy page: “Ann Mason”. So far, I have been unable to connect any Masons to the Meymott family, so Ann Mason remains a mystery.

Image from Margaret Cavendish’s ‘Orations’, 1662

Latin Translation

What makes this copy most fascinating is its annotations, largely in Latin.

Image of the title page of Margaret Cavendish’s ‘Orations’, 1662. The title page is covered in short Latin phrases.

Margaret Cavendish didn’t speak Latin, but she wanted her books translated into this international language of scholarship so that her ideas could be spread on the continent. The prefatory poem written by her husband in praise of the book declares her ambition to have her works read in “All Europ’s Universities”. However, only one of her books, her biography of her husband, was ever fully translated into Latin and printed.

Chatworth’s copy of ‘Orations’ features extensive marginal notes that translate some of the speeches into Latin. Other pages don’t contain full translations but contain notes that suggest the beginnings of translations.

Images from Margaret Cavendish’s ‘Orations’, 1662. From left to right, p.1, p1 (closer), p.138, p.198, p.251.

It’s difficult to say with certainty who made these annotations. Clement Ellis certainly knew Latin, and in 1675 he printed a Latin grammar that he’d written for his children. It’s possible that Margaret Cavendish could have asked him to translate the text for her, or perhaps Ellis could have undertaken the translation to impress his employers if he knew of her ambitions.

If so, Chatsworth’s copy of ‘Orations’ is evidence that other translations of her work were begun, even if they were never completed or printed.

Corrections and Revisions

This copy of ‘Orations’ also contains some annotations in English, largely revisions to the English text.

Margaret Cavendish often had mistakes in her books corrected by hand before they were distributed. These uniform corrections appear in copies of ‘Orations’ held in other libraries and are also apparent in Chatsworth’s copy.

Images from Margaret Cavendish’s ‘Orations’, 1662. From left to right, n.p. and p.115. In the first photo the “C” in “Praefactory” has been crossed out to correct the word to “Praefatory”. In the second, “Mollits” has been corrected to “Mulcts” (meaning “a fine”), and “Council-Table”, changed to “Council-bord”.

Other revisions to the English seem to have been made by the same person as the Latin translation. Maybe rewriting certain English phrases helped with the translation, or perhaps these phrases just struck the annotator as clumsy.

Images from Margaret Cavendish’s ‘Orations’, 1662. From left to right, p.4 and p.6.

This copy of Cavendish’s ‘Orations’, seemingly owned and possibly translated by someone who knew her, is a fascinating and exciting insight into the reception of one her books. Who knows what further research could reveal.