Over the past three months Frankie Drummond Charig, Project Archivist at Chatsworth has been preparing the online catalogue of the Hardwick Manuscripts, ready for it to be added to the Archives Hub and The National Archives Discovery. The cataloguing of the Hardwick Manuscripts down to item-level makes it easier for researchers to find what they’re looking for online and will hopefully make these papers more accessible.

Here Frankie outlines a few of her favourite items she's catalogued from the collection.

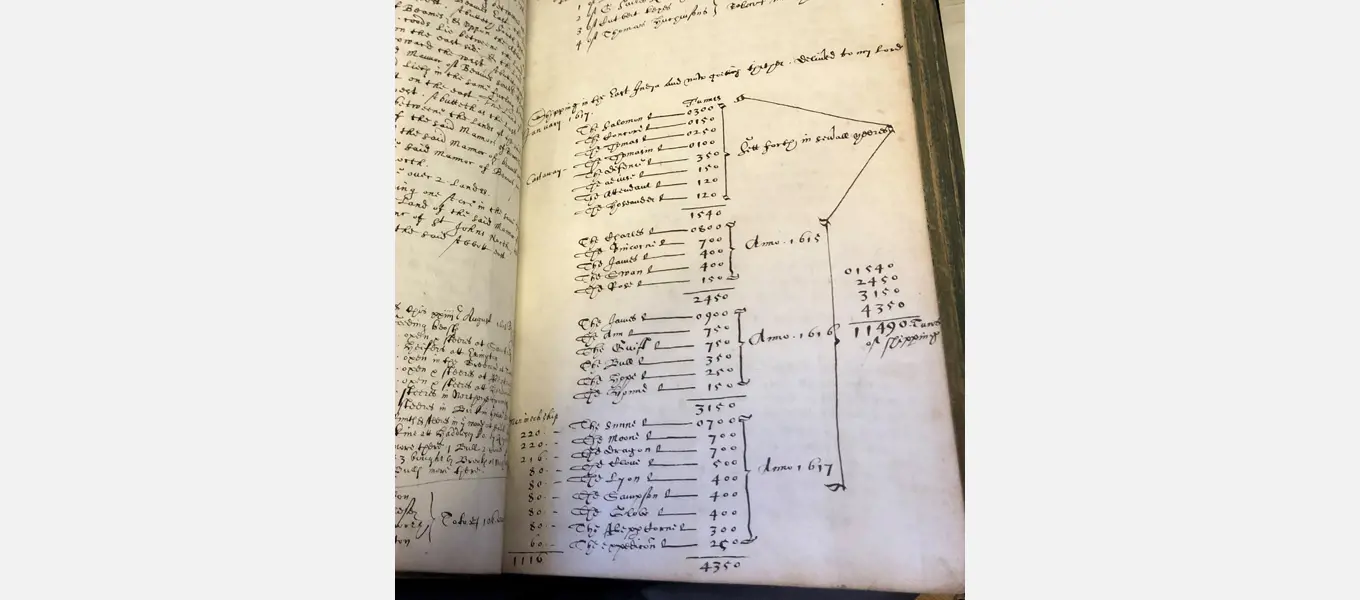

Memoranda book of deeds relating the Cavendish family 1616-1703 (Hardwick MS 87) (HMS/2/15)

This very large volume (over 800 pages!) contains copies of important deeds, wills, letters patent and memoranda relating to lands, livestock and goods at Hardwick and Chatsworth and other estates of the Cavendish family during the 17th century. It seems to have functioned as a place to record and copy any important information regarding these topics that needed overseeing or remembering to the family and estate managers (called Receivers). The volume is written in several scribal hands and entries recorded span several decades.

Many country houses are currently exploring historic links with the East India Company, and there is a sequence of more informal entries made between 1616 and 1618 which includes a list of ships of the East India Company and the amount they shipped and delivered to Sir William Cavendish (later 1st Earl of Devonshire) between 1615 and 1617. We can see from this list (on the right-hand page) the names of the ships, how many tonnes of cargo Cavendish received from them, in which years and even how many “men in each ship” (meaning “crew”) there were in 1617. This brief note shows us just how invested Cavendish was in the Company. Whilst the account book for this period (1608-1623, Hardwick MS 29, HMS/1/16) shows us how much Cavendish invested in overseas adventures and the brief book of receipts (1618-39, Hardwick MS 27, HMS/1/18) gives us an overall amount he received in return on his investment once cargo was sold, this record here gives us more detail of the stage between money being invested and investment returned.

I particularly love records that show the humans behind the records that have outlived them. The following are examples of these:

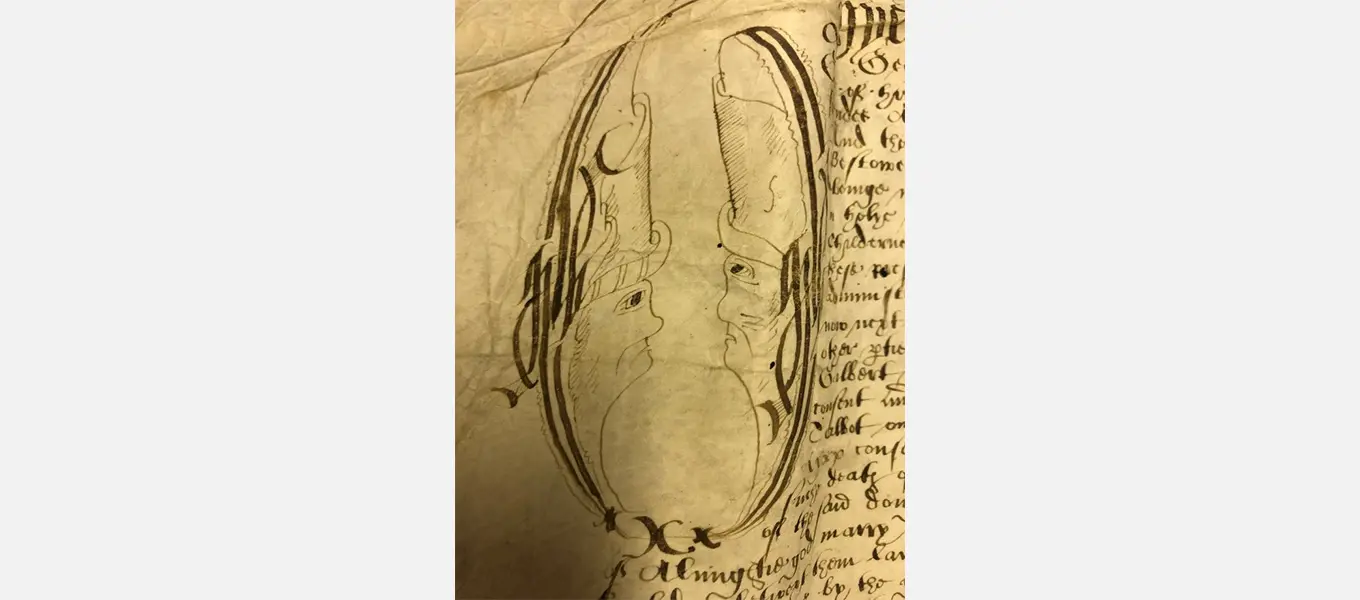

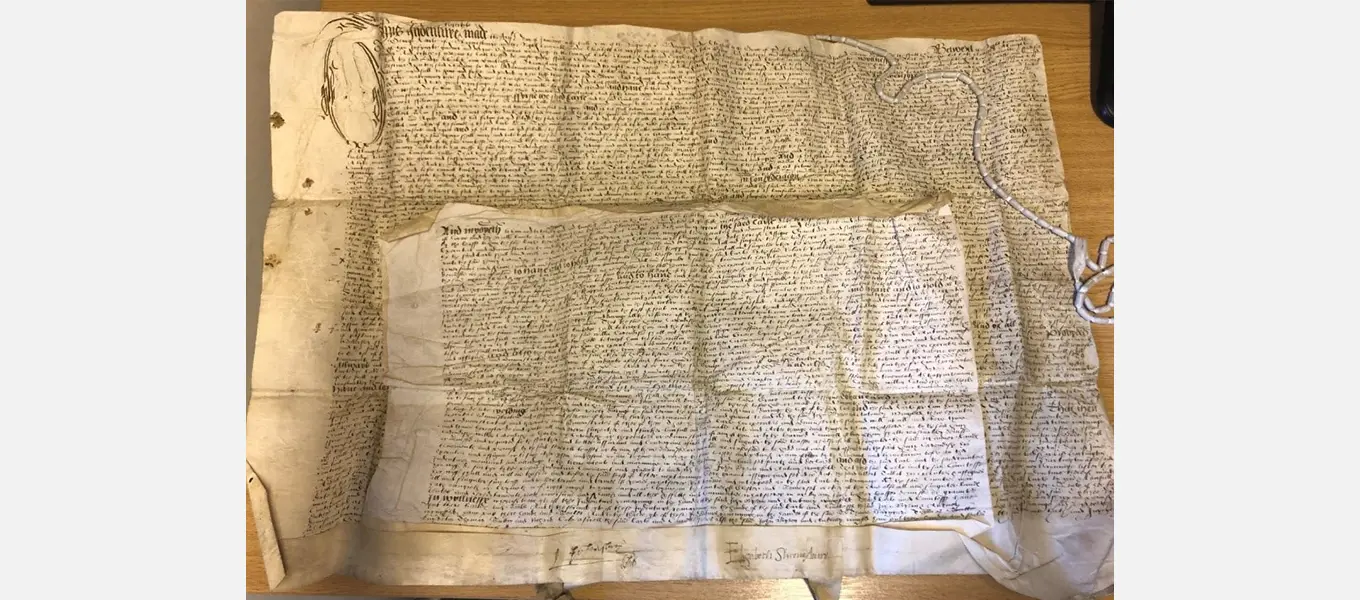

Settlement prior to the marriage of Gilbert Talbot with Mary Cavendish and Henry Cavendish with Grace Talbot, 7 January 1568 (HMS/5/4)

The scribe for this indenture has chosen to draw a particularly detailed and playful letter ‘O’ for what is otherwise a very dry, formal and turgid document (nonetheless incredibly important in securing the future inheritance of Bess of Hardwick’s children and their heirs to follow). The whole document runs over one and a half pieces of parchment half a metre in width.

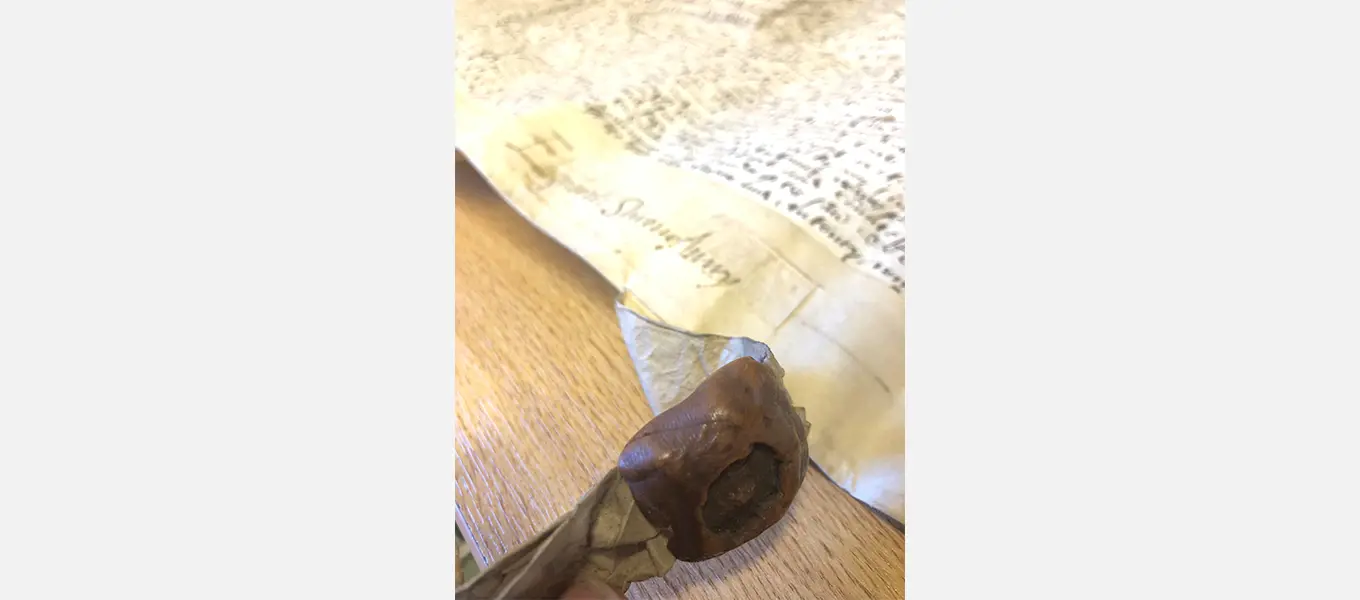

You can see the signature of Bess and her husband George Talbot at the bottom, underneath which their seals are attached. Bess’s seal has a visible fingerprint mark in the wax where it was pressed onto the parchment whilst warm – a 453-year-old fingerprint still visible today!

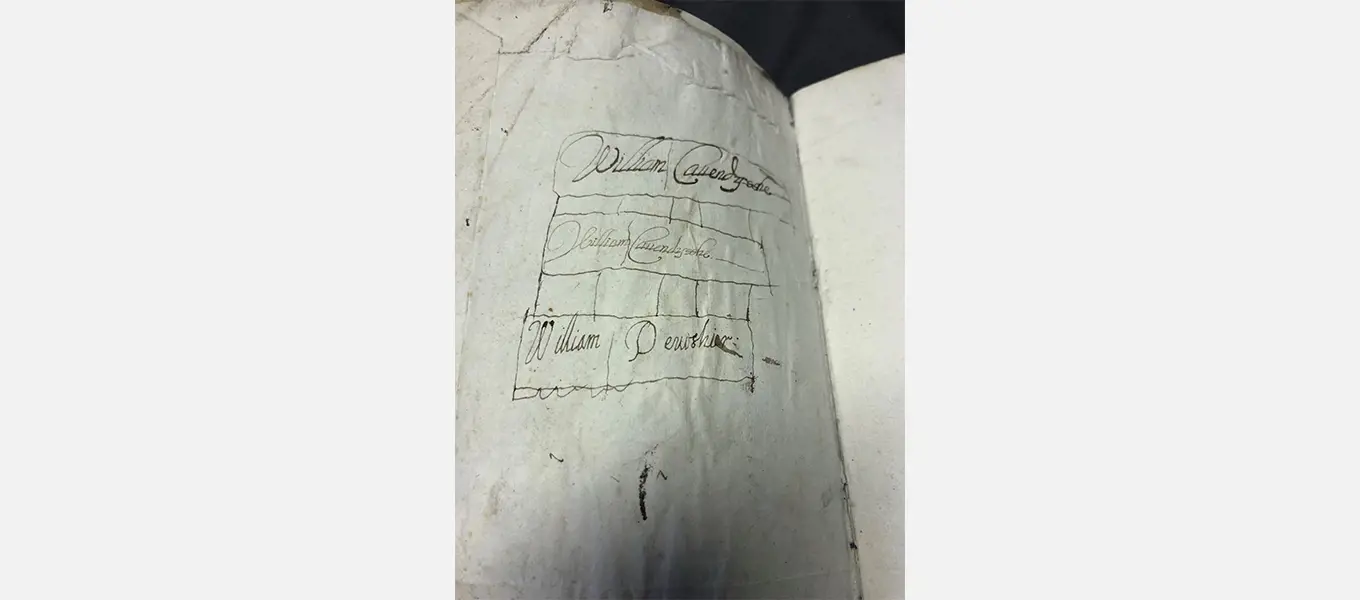

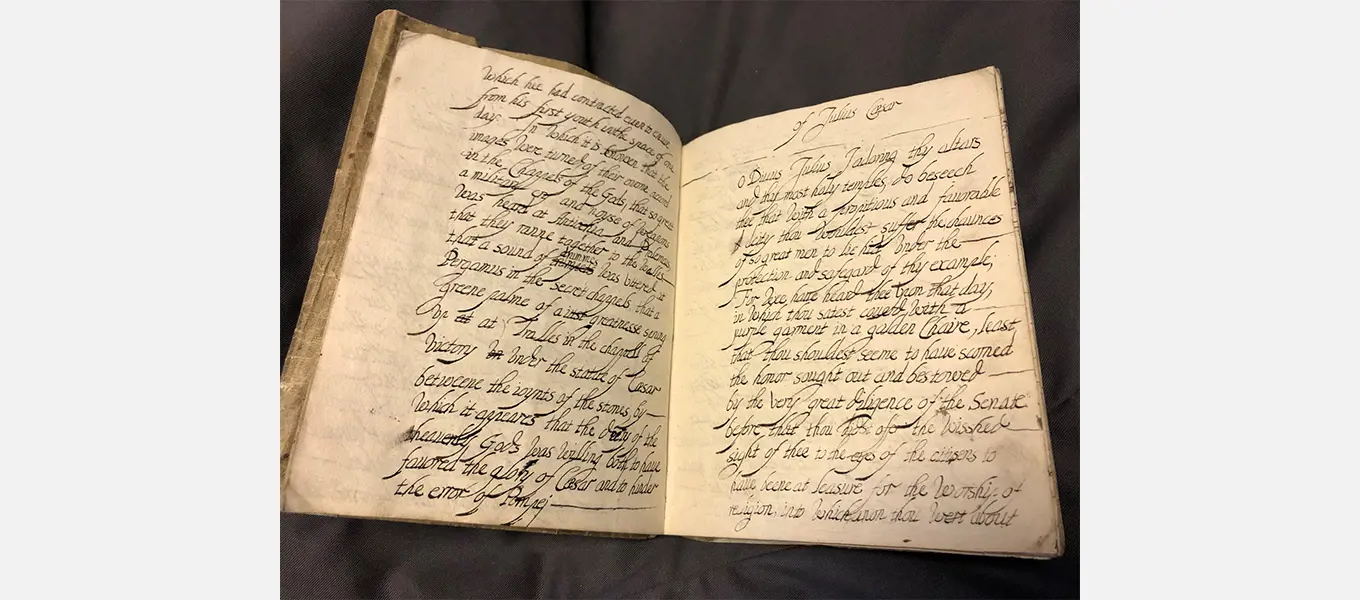

A book of abstracts from Roman history written by Charles and William Cavendish (Hardwick MS 70) (HMS/4/34)

Among the manuscripts in this collection are a few exercise books thought to belong to young male Cavendishes.

This exercise book was used to record histories of eminent Romans including philosophers and Roman stories. It was likely part of the education of the 2nd Earl's sons, William Cavendish (1617-1684) – who would become 3rd Earl – and Charles Cavendish (d. 1643). On the outside cover "W. Devonshire and Charles Cavendish his book" is very faintly visible. Inside the cover the name “William Cauendysshe” is written several times in a shaky childish hand, and the back cover includes the same, followed by: "William Devonshier" – the name the young heir received on the death of his father. In William’s case this occurred when he was just 11 years old. Could this book be contemporary with this event in William Cavendish’s life? Perhaps the added signature in the back of his book hints of a child contemplating his future as the next earl.

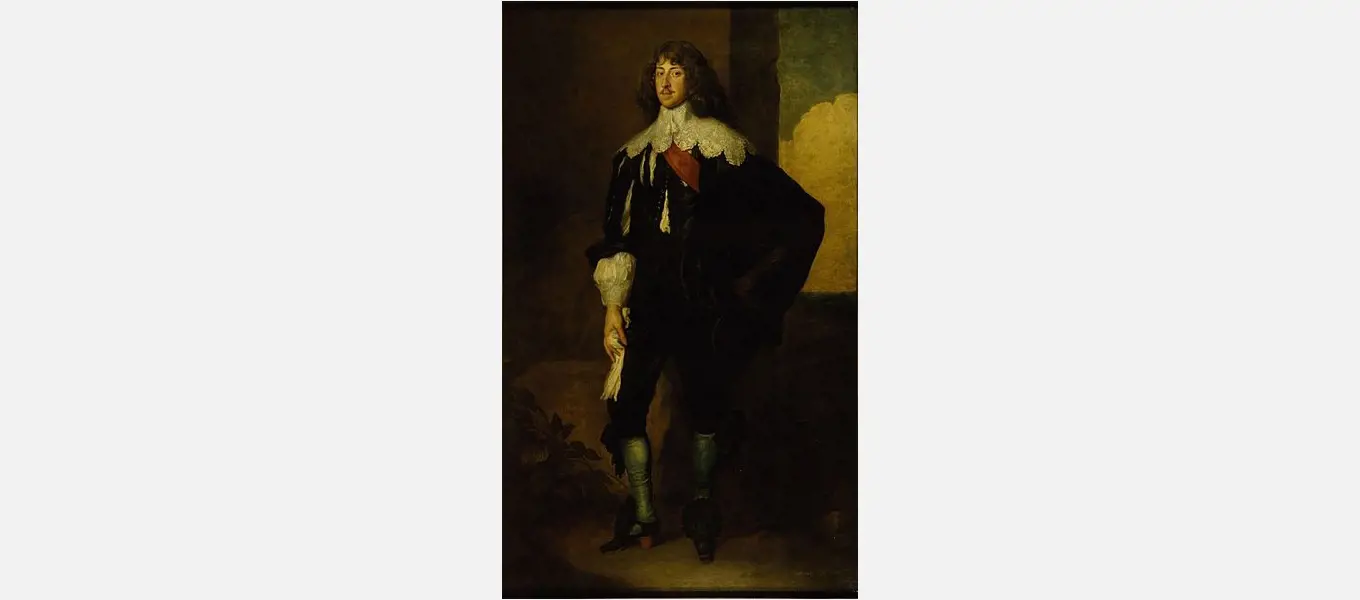

The 3rd Earl went on to become a very astute and involved manager of his estate and guided by his mother Countess Christian’s good example, he was particularly adept at managing his finances. This is clear in the number of account books emblazoned with his signature and austere comments, as well as his location when checking the account. He notes when totals don’t add up, when bills have been written into the wrong account book or already paid and most often when he believes the expenses are too high. Sometimes he even refuses to pay certain items altogether. He quibbles over the cost of a gardener, the length of board wages, the price of horse feed compared to London prices – nothing got past him. All these small notes add up to present quite a picture of the Earl’s character and what it must have been like to work for him.

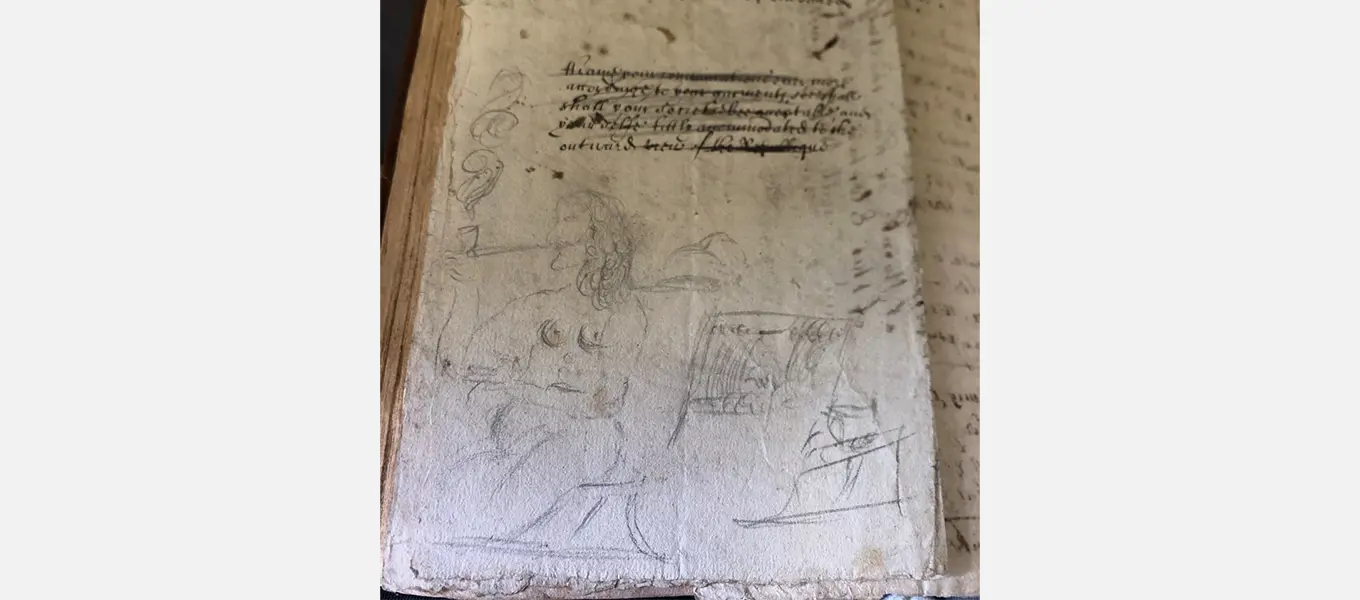

I do wonder if a sketch in one the account day books (HMS/1/29) might have something to do with the Earl… The drawing is of an unknown character by an unknown artist. But it could be the handiwork of Humphrey Poole, Receiver for the Derbyshire estate, who drew and annotated papers a lot and whose writing is visible above this sketch.

William Cavendish, 3rd Earl of Devonshire, by Anthony Van Dyck, 1638