Frankie Drummond Charig, Project Archivist, shares a recent discovery amongst the letters of the 4th Duke of Devonshire that may elucidate how some black military drummers came to be in Ireland in the 1750s and beyond.

Figure 1: The entrance to Waterford Harbour by T.S. Roberts, printed by J.W. Edy, 1791 (British Library)

Around 1804, Henry Tite was born in Waterford, Ireland. Having been a labourer, at the age of 21 he enlisted in the 29th Worcestershire Foot Regiment on 23 October 1825, where he remained until 1830[1].

There is a letter in the National Archives of Ireland referring to Tite’s request for leave to testify as a witness to a robbery that occurred in Tallow[2]. Other than this letter and Tite’s army records, there is little known about him. He may have married Catherine Tobin on 9 January 1825[3] - perhaps the same Catherine Tite who was also born in Waterford around 1806 and who died there as a “widow of a servant” in 1860.[4] Possibly John Tite who moved from his birthplace of Waterford in 1833 to Liverpool and then Manchester may also have been a relation. But we may never know. Such is the uncertainty and silence created by the Archive.

Henry Tite’s army enrolment record from 1825 tells us that he was a black man, with black hair and eyes and a round face. How had a black man come to be born in Waterford, Ireland in the early 19th century? And how does his story relate to the Chatsworth Archives?

Figure 2: Enlistment record for Henry Tite (TNA W0 25/364)

It’s important when stories of people of colour are present in the archive, yet haven’t always made it to secondary resources or into general awareness and understanding of history, that we draw them out and illuminate these individuals who did exist and are part of the history of these places. Sometimes stories from the archive are problematic, sad, incomplete and frustrating but not sharing them might suggest they were never there, which is not the case at all. The incomplete and problematic nature of the records and the silences of the archive is perhaps a matter for another blog…

Henry Tite may seem an unusual example, but in fact the 29th Worcestershire Foot Regiment by the time of Henry’s enlistment, had an almost fifty-year tradition of enlisting black and brown men as drummers for the regiment.[5] Drummers were paid the same or better than those wielding arms and were responsible for signalling events and commands, and providing cadence for marching.[6] They were also responsible for carrying out floggings.[7]

The first reference to black men being enlisted into the 29th Worcestershire Foot Regiment was, according to Major H. Everard’s history of the 29th Regiment, around 1759. [8] However, J. D. Ellis has pointed out that it must have been before this due to discharge records showing some of these men with years of service at their discharge, which meant they must have enlisted before 1759.[9]

Henry Tite and another, George Carville are unusual in this group of drummers because of their birthplace being Ireland. Records show that most of the black and brown drummers from the 29th regiment were born on the African continent and in the Caribbean Islands and South Asia.

What is not always clear from looking at enlisting records is how these men made their way to Britain and to what extent their enlistment was voluntary. Ellis’s article discusses the issue of voluntary enlistment and the benefits of enlistment in more detail and can found online for free.[10]

However, a letter recently catalogued at Chatsworth may shed some light on the ‘how’ or possibly even provide evidence of the beginning of this tradition of enlisting people of colour as drummers.

In May 1756 Lord Frederick Cavendish had been seconded to the 29th Regiment as Lieutenant-Colonel which was stationed in Ireland. He writes to his brother, William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire and Lord Lieutenant of Ireland concerning a French ship that has been brought into Waterford by pilots (mariners who manoeuvre ships through busy waters). The ship was travelling from “St Domingo” (whilst Santo Domingo, is the capital of modern-day Dominican Republic this was probably a reference to “St Domingue”, now modern-day Haiti) carrying coffee, sugar and indigo from the French colonial plantations to Bordeaux in France with “28 hands, two French and three Portuguese passengers”.[11] This being during the time of the Seven-Years-War, Lord Frederick was not likely to let the ship replenish supplies and be on its way. He writes to his brother that he suspects the captain has embezzled some of the cargo (going by the still-visible original waterline on the ship). And then enters into a long reflection on the “striking of the colours” (the surrender of the ship) and who should lay claim to the cargo. He adds: “the poor pilots, in equity, have the best right, yet I doubt they will not get it, it matters not who gets her, the 29th [regiment] have got their share, in making a prize of three fine little Black boys, but mum about that, for ‘tis a great secret I entrust you with”.[12]

Referring to these black boys as a “prize” in the same sentence as mentioning the claim to cargo frames them as property, regardless of whether they were officially “free” or enslaved. They were spoils of the war, rather than passengers to be let on their way. It’s an uncomfortable sentence to be faced with, perhaps especially if our skin matches that of those boys or other marginalised races. It may stir feelings of embarrassment or guilt if it’s white, but that is not helpful if it deters a continued enquiry into the story – in an endeavour to make clearer the faces of the past.

Figure 3: Letter from Lord Frederick Cavendish to William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire, (Chatsworth Archive, CS4/236)

Figure 4: SANTO DOMINGO, (Dominican Republic) city plan map, c 1750 printed by Pierre Quentin Chedel

What happened to those boys? Why did Lord Frederick want them kept as a secret in that moment?

Lord Frederick’s later letters don’t mention the black boys again. However, he makes explicit in his letter that he intends them for the 29th Regiment. Additionally, perhaps we can draw on what we know of the 29th Regiment’s history from the 1750s onwards of enlisting black and brown men as drummers. Ellis suggests that like black servants who were often seen as a status symbol in the 18th century, black drummers in the 29th Regiment may have “enhanced the prestige and status of the 29th”.[13]

Did Lord Frederick wish to keep the black boys a secret until he had acquired the King’s permission to enlist them for his regiment? In 1759, George Boscawen was supposedly given permission by the King to enlist ten black youths from Guadeloupe into the 29th regiment.[14] Boscawen took over the regiment shortly after Lord Frederick and it was Lord Frederick who had recommended George Boscawen as Lieutenant for the 29th Regiment, on his own promotion to another in July 1756.[15] This suggests that they had a rapport. Perhaps these ten black youths in 1759 were joining three others who possibly enlisted three years earlier, when the 29th was under the command of Lord Frederick.[16]

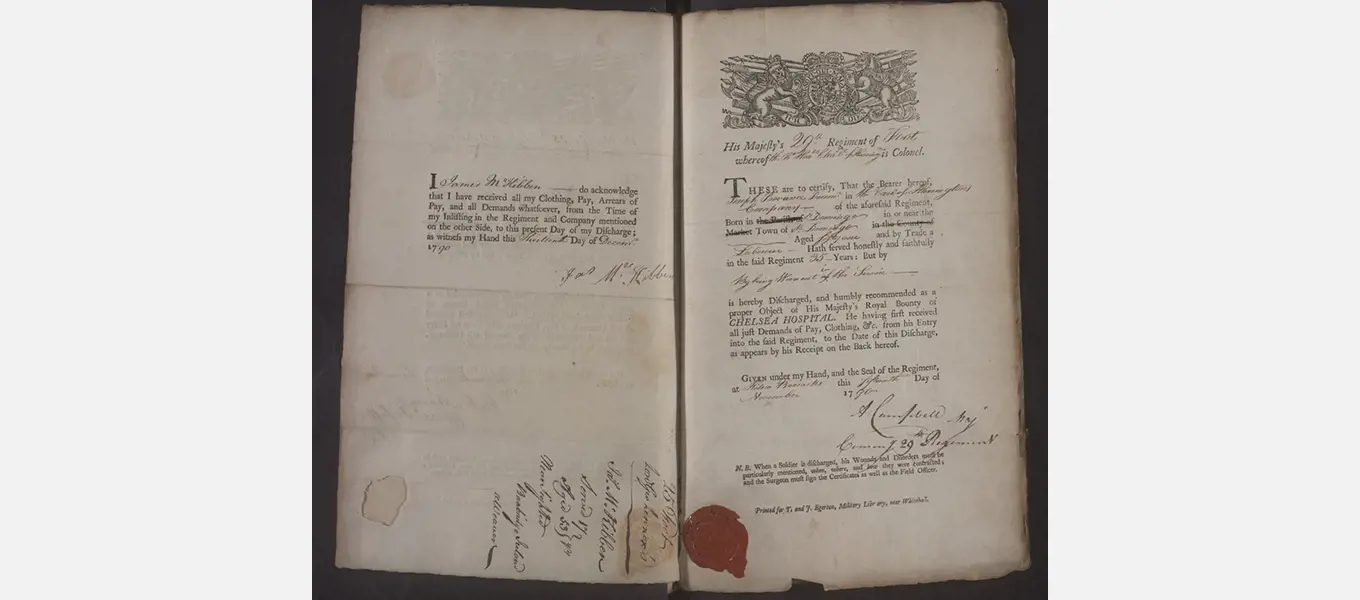

In his work on this topic Ellis has identified a man named Joseph Provance as one of the people who was likely enlisted into the 29th Regiment before 1759.[17] Ellis tells us that Joseph Provance (probably not his original name) was discharged with a pension in 1790 at the age of about 51 after 35 years’ service.[18] This would have made him around 16 in 1756, and his enrolment as occurring around 1755/6. Additionally his army record identified him as “a labourer of St Domingo”. Could this man be one of the boys who arrived on the French ship in Waterford? Is this the story of how Joseph Provance came to be in Ireland? Since his article, Ellis has also discovered that a Joseph Provence, aged 74 years, was buried at St Martin-in-the-Fields, Westminster, on 14th January 1818. He adds, “It was noted that he was settled and renting in “Off Alley”. Quite a few of the Black veterans settled in London - close to the RH Chelsea (who provided daily meals for out-pensioners) and other veterans”.[19]

Figure 5: The pension record for Joseph Provance showing 35 years' service to the 29th foot, in 1790 (Wo 121 - Chelsea: Pensioners' Discharge Documents 1760-1887)

If this is the same Joseph Provance, he would have in fact been 46 at his discharge and only twelve in the year that three black children arrived in Waterford port on a ship hailing from St Domingo.[20] The discrepancy between Provance’s age recorded at his discharge compared to that at his death could perhaps be explained by the fact that it was preferred to enlist boys over the age of sixteen and his age may have been increased at enlistment for this reason. [21] Or, there may have been a presumption about his age, if he ‘appeared’ older than he was.

Ellis notes that records show how second generation black soldiers followed their fathers into enlisting in the 18th century. [22] Was this the case with Henry Tite, born in Waterford? No other Tite from Waterford has appeared in my rudimentary searches of military records, but could one of the black boys who arrived on the cargo ship from St Domingo into Waterford perhaps have stayed in Waterford and later had Henry? We may never know. But the history of the 29th Regiment enlisting black and brown drummers from the mid-18th century and that French ship arriving at Waterford with three black boys on board being met by Lord Frederick, Lieutenant-Colonel of the 29th Regiment, seems too coincidental to be ignored. Perhaps we can name one as Joseph Provance.

The existence of these letters provides evidence where we may not have had any that those black boys arrived in Waterford in 1756. And conceivably the great-great grandchildren of those people may be walking around today, waiting to discover who they came from, which often starts with a name.

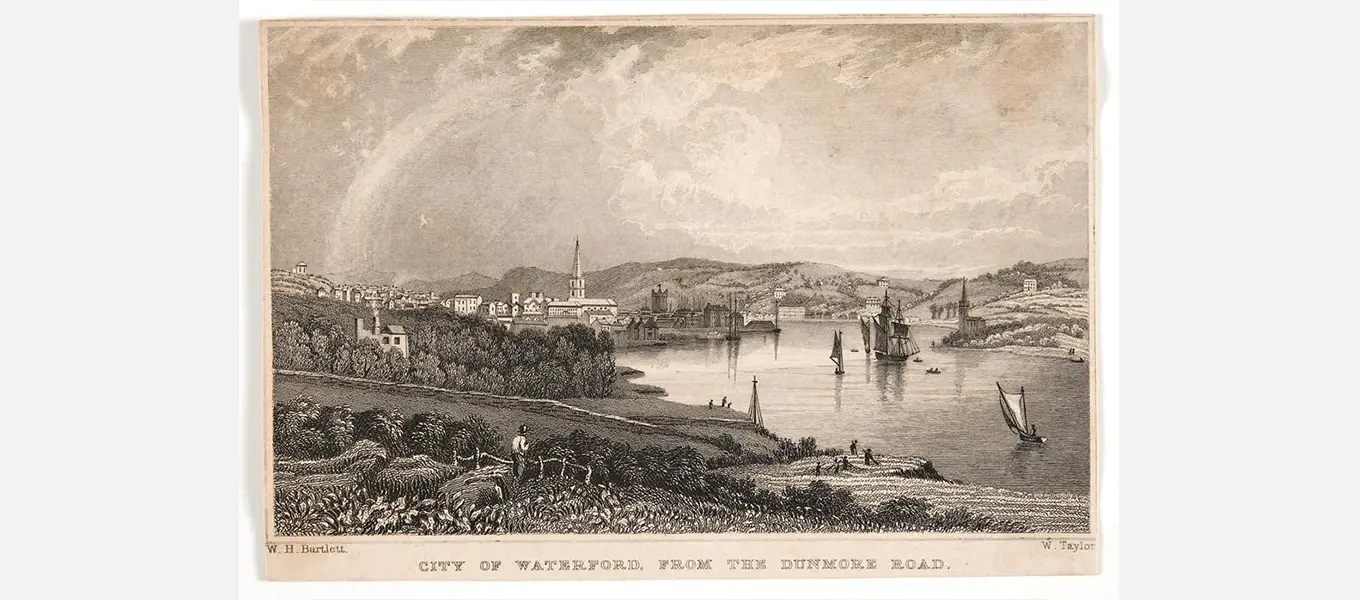

Figure 6: A print of the City of Waterford in 1831, engraving by W. Taylor from a print by W.H. Bartlett © Ireland Illustrated

Read about The Devonshire Group's ongoing academic research into archival links with colonialism on the Devonshire Group website.

References

[1] Enlisting record for Henry Tite: TNA, WO25/364; Discharge record for Henry Tite: WO 97/483/47.

[2] National Archives of Ireland: CSO/RP/OR/1826/106, Letter from [Henry] Gumbleton, Carriglass House, [County Waterford], reporting that Henry Tite has sworn information against Peter Halpin, accusing him of participating in the robbery of Mr Boyces house in Tallow.

[3] Catholic Parish Registers, National Library of Ireland; Dublin, Ireland; Microfilm Number: Microfilm 02470 / 06.

[4] Ireland, Civil Registration Deaths Index, 1864-1958.

[5] J. D. Ellis, “Drummers for the Devil? The Black Soldiers of the 29th (Worcestershire) Regiment of Foot, 1759-1843,” Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, 80 (2002), 187.

[6] Don N. Hagist, https://allthingsliberty.com/2022/02/black-drummers-in-a-redcoat-regiment/

[7] J. D. Ellis, 2002, 194.

[8] H. Everard, History of Thos. Farrington's Regiment Subsequently Designated the 29th (Worcestershire) Foot 1694-1891, Naval and Military Press, (reprint 2014).

[9] J.D. Ellis, 2002, 188, examples of men who likely enlisted before 1759 include John Charloe and Joseph Provance.

[10] See Ellis’s 2002 article here: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44230826?read-now=1.

[11] Chatsworth Archive, GB 2495 4th Duke’s Correspondence, CS4/235.

[12] Chatsworth Archive, GB 2495 4th Duke’s Correspondence, CS4/236.

[13] Ellis, 2002, 188.

[14] The Black Drummers of the 29th Foot Regiment, http://www.worcestershireregiment.com/black_drummers.php

[15] GB 2495 CS4/280.

[16] There are no enlistment records for the 29th before the 1760s which is why we cannot say categorically, and have to go by pension and discharge records for enlistment dates.

[17] Ellis, 2002, 184.

[18] Ellis, 2002, 200.

[19] Email correspondence, J.D. Ellis and FDC, 23/03/2022.

[20] Westminster, Poor Law And Parish Administration. City of Westminster Archives Centre. 1818.

[21] A letter from Lord Kildare to the 4th Duke of Devonshire, 24 August 1756, written from Dublin, in which he states that the King does not approve of enlisting boys under the age of 16 into the forces (Chatsworth Archives GB 2495, 4th Duke’s Correspondence, CS4/317).

[22] Ellis, 2002, 189.