Watch

In this short film, Katherine Hardwick-Kulpa, Assistant Curator, tells the story behind Chatsworth's majestic lion sculptures.

Read the transcript below:

As you walk through Chatsworth’s Sculpture Gallery, your eyes are drawn to two towering figures at the far end — two majestic lions.

These sculptures aren’t just decorative pieces; they carry with them a story of art, admiration, and an enduring friendship between two extraordinary figures of the 19th century: the Italian sculptor Antonio Canova (1757-1822) and the 6th Duke of Devonshire (1790-1858).

Above: portraits of Canova (left) and the 6th Duke (right).

These lions were commissioned by the Duke in 1823, just months after Canova’s death. The Duke had long admired Canova’s work, and these sculptures were a tribute to the artist’s genius.

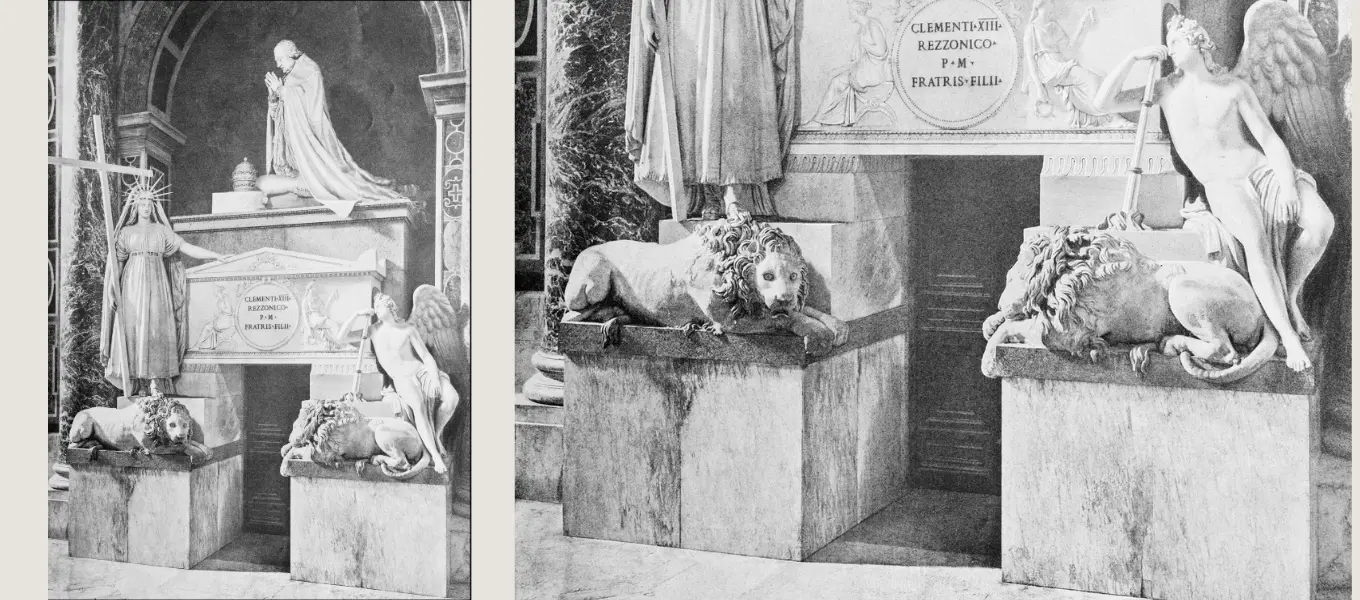

Their creation was entrusted to two of his most talented pupils, Francesco Benaglia and Rinaldo Rinaldi. Using casts taken from Canova’s original lions, the pupils crafted these sculptures as faithful copies of Canova’s masterpiece — two lions that flank the tomb of Pope Clement the Fourteenth, in St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City (below).

Canova’s studio in Rome was a hub of creativity, where some of the most celebrated sculptures of the time were created. It was here that Benaglia and Rinaldi worked, using Canova’s tools and methods to bring the lions to life (below).

The first lion is asleep — reposed and majestic, a symbol of power at rest. Canova had an unparalleled gift for capturing emotion and form in his sculptures. This sleeping lion, with its muscles relaxed and expression serene, radiates a sense of calm confidence.

The second is poised and alert. Its muscles tense, its gaze sharp — as if it’s just about to leap into action. Together, these lions symbolise the duality of power: one resting in assured dominance, the other vigilant and ready.

Once at Chatsworth, the lions were placed at the end of the Sculpture Gallery, beneath portrait medallions of Canova and the Duke. This was a deliberate choice by the Duke, whose admiration for Canova extended far beyond the sculptures.

He once described the artist as "the most talented, the most simple, and the most noble-minded of mankind."

The placement of the lions beneath their portraits symbolises this deep connection — an artistic tribute, yes, but also a memorial to their friendship.

The lions are not the only masterpieces by Canova in this gallery. The 6th Duke's collection includes several other works by the famed sculptor, like the bust of Napoleon and the striking portrait of Madame Mère, Napoleon’s mother.

Finally, the sleeping Endymion (below); a piece that embodies Canova’s gift for capturing the human form in marble.

The 6th Duke’s devotion to Canova’s memory went even further. Along with these sculptures, he acquired Canova’s tools — those humble instruments that transformed raw stone into life-like sculptures.

These tools, a tangible link to the artist’s hand, are now displayed nearby, enshrined like relics in a small glass case; carefully preserved, as if they too carried a piece of Canova’s spirit (below).

As they stand proudly once again in the Sculpture Gallery, the lions are more than just an artistic display. They are a tribute to a friendship that transcended borders, rooted in a shared passion for beauty and craftsmanship.

For the Duke, Canova was not only a master artist but also a personal hero — a man whose talent was matched only by his nobility of character.

These lions stand as a lasting reminder of the power of creativity and the bonds it can forge.

Header image: "'Antonio Canova sculpteur', d'après Sir Thomas Lawrence. Musée du Louvre." by Lejeune Grégory is marked with CC0 1.0.

Sketch of Antonio Canova's Studio, Chiarottini Francesco 1786, (c) Udine Castle

Images of Chatsworth's Sculpture Gallery: David Vintiner and India Hobson

Portrait of the 6th Duke of Devonshire by Sir George Hayter (1792-1871), 1816, copyright Devonshire Collections, Chatsworth