The strange-looking object in the image below, currently stored outside the old Laundry at Chatsworth and long assumed to be something to do with dairy churning is, in fact, a light dimmer. To be precise, it is an 'electrical liquid resistance dimmer' for theatre lighting from the 1890s.

When in use, the ceramic tube would be filled with a conductive liquid, with one electrode fixed at the bottom of the tube, and another attached to the lever so it could move easily through the liquid.

When hooked up to electricity, the brightness of a stage lamp was controlled by the proximity of the top electrode to the bottom one: the closer they were, the brighter the lamp (1). But this dimmer is so much more illuminating than it seems. Beyond its practical use, it represents a fleeting convergence of the histories of theatre and the country house - two worlds united in one moment by their technical ambition. It’s this ambition that’s enshrined in Chatsworth’s Theatre and embodied by this otherwise innocuous dimmer.

Above: An electrical liquid resistance dimmer, used in the Chatsworth Theatre from 1896. Supplied by Drake & Gorham. Patented by Lyon’s. Image: Aidan Haley.

The conversion in January 1896 of Chatsworth’s former Ballroom into a theatre was a huge undertaking. Not only did an entire stage have to be constructed, with all its attendant fixtures and fittings, but the room was to be lit by electricity.

Only installed in parts of the House a few years earlier, electricity had to be extended to the room from the main building. Around a thousand yards of cable was ordered, along with lamps, switches, brackets, fuses, pulleys, and a counterweight. The invoice from supplier Drake & Gorham extends to over four pages and, including the labour to install it all, amounts to £202 and 8 pence - the equivalent today of around £17,000.

Our dimmer was one such item on this invoice, priced at £8 and 5 shillings - about £700 in today’s money. Drake & Gorham were not the only suppliers of new lighting equipment: a firm of metal workers provided an additional set of five long electrical battens which would light the stage from above. The full kit took over three weeks to install, employing at least seven men and bringing electric light to both the auditorium and the stage.

It’s quite something to imagine all the activity taking place in this one room. Alongside the installation of all this cable - while porcelain ceiling roses were being fixed in place and frosted tulip shades attached to lampholders - a further 33 men were employed in the construction of the stage itself. They were carpenters, joiners, plasterers, blacksmiths - all local and all engaged in the shared ambition of building a perfect, miniature theatre. Among a hundred other tasks, they were responsible for installing the painted proscenium arch that you see today, and for ensuring the smooth rolling of Chatsworth’s unique front cloth - a mechanism that is surprisingly fiddly because it has to roll from the bottom.

Like many historical events at Chatsworth, this was all achieved in record time: work started on the old Ballroom on 16 December 1895, and the first performance took place in the new Theatre on 27 January 1896. That’s exactly six weeks.

To put this theatrical investment in context, the story of technical advancement in country houses is sporadic and often reflects changes in individual fortunes. When we do see upheavals to technical systems, we can assume a significant financial investment has been made, and it’s widely understood that this was usually to improve the comfort and convenience of those who lived in the house.

As examples, I would invite you to think of the variety of bell systems you might have seen to summon servants; or, the range of washing facilities, reliant on the introduction of running water for improved sanitation; or, the evolution in food heating appliances to keep dishes warm on their journey from kitchen to dining room (2).

Meanwhile, in theatres, technological investment was necessary for financial sustainability. It was in their financial interest to capture and hold an audience’s attention, to attract and build audience numbers.

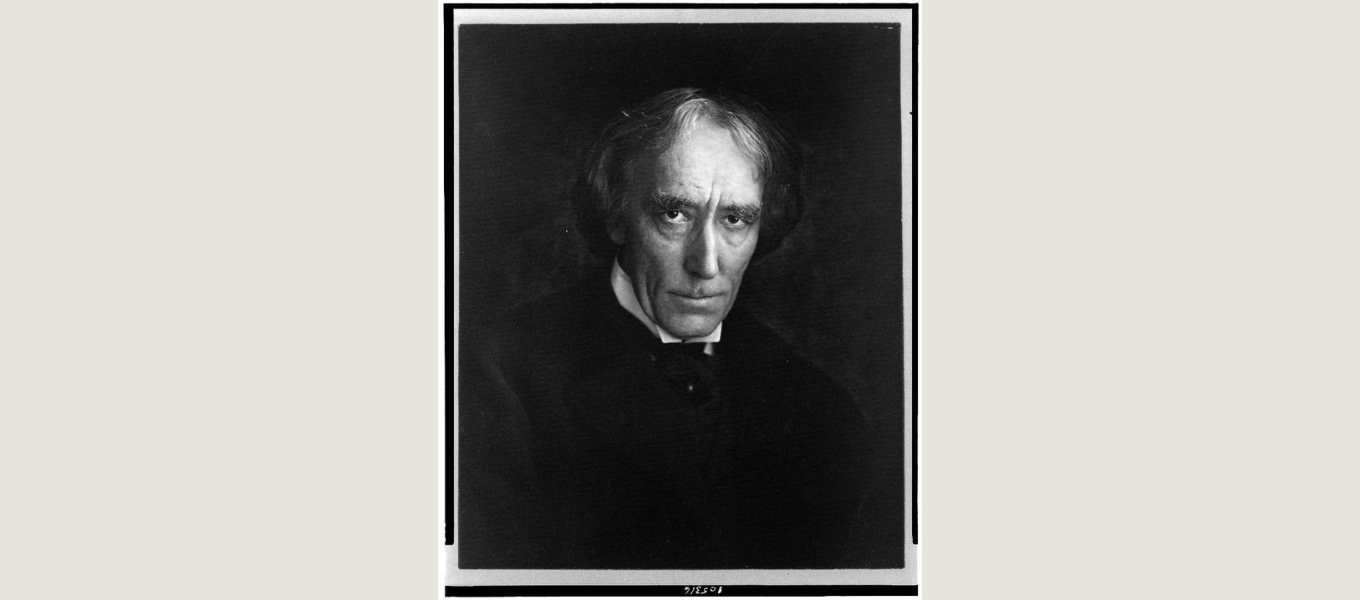

One of the ways they did this was to experiment with emerging technologies. The manager of the Lyceum Theatre in London, Sir Henry Irving, was a pioneer in this field. It was Irving who first dimmed the lights in the auditorium during a performance, and it was Irving who introduced stagehands dressed in black to undertake highly choreographed scene changes - a process that relied on the careful control of artificial light to veil backstage activity, rather than mechanically dropping a front cloth between acts.

Above: Sir Henry Irving c. 1900. Image © Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (LC-USZ62-105316)

Yet it was not Irving who first embraced the theatrical shift from gas to electric lighting - and perhaps for good reason. This accolade went to the Savoy Theatre, lit solely by electricity in 1881. Yet, by one account, ‘it was not till about 1891 that electric-light was, even in a crude condition, forward enough to be used for general lighting purposes in British theatres' (3).

That Chatsworth’s Theatre was lit entirely by electric light from January 1896, then, tells us two things: first, that the family valued the role of theatrical entertainment so highly that it was prepared to extend its investment in new technology for this sole purpose; and, second, that in doing so, it was at the vanguard of ambitious theatrical technology as well.

But what of our dimmer? As suggested here, the archival records tell us that a lot of artificial light was brought into this resurrected room. The stage itself also suggests there was more: you may notice that the middle section at the front of the stage protrudes further than the rest. This was where the footlights were located. Explore under the stage with a torch and you can see the original electricity points that powered these lights: pipes that encased cables snake away into a shallow void. All these lights and only one dimmer. What did it do? Which lights did it dim?

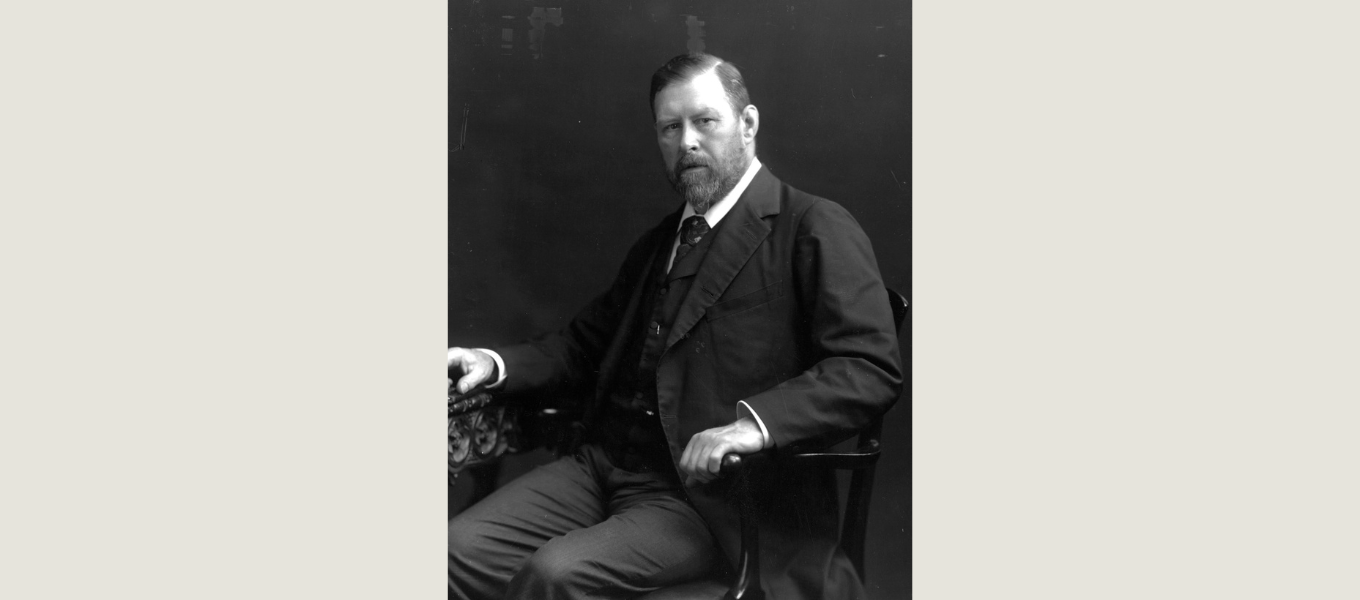

Bram Stoker, author of Dracula and Irving’s business manager at the Lyceum, wrote that Irving began experimenting with electric light by degrees. Accustomed to the quality and manipulation of light produced by gas, electric light was something of an unpleasant contrast. It is understood that ladies in country houses experienced something of the same discomfort, finding the new electric lights to be harsher on their complexions. For this reason, even though electric lights may have been introduced for general lighting, long dining tables, heavily laden for grand dinners, continued to be lit by candles (4).

Irving eased his way into electric light by using a similar blend of lighting sources. According to Stoker, unless the bulb was tinted, when theatrical electric light was dimmed it changed colour. Adapting to this and understanding its possible applications required some level of experimentation. Irving’s first foray into electrical light was with dimmable footlights. ‘The purpose of lowering footlights,’ Stoker tells us, ‘is to create a scenic atmosphere of night or mystery or gloom’ (5). It’s possible that this row of lights lent itself to effective experimentation because of its particular atmospheric qualities. Regardless, the only way to lower electric footlights...a resistance dimmer.

Above: Bram Stoker c. 1906.

Was our dimmer used to control the intensity of the footlights in Chatsworth’s theatre? Or, with so much electric light installed in the auditorium, did it employ Irving’s tactic of slowly bringing the audience into darkness? It was an expensive item on the original invoice - whatever use to which it was put was deemed important enough to invest in.

Reconstruction videos now show these early liquid resistance dimmers to be dangerous and to require a lot of maintenance. Stoker, too, writes of them as being ‘a wasteful as well as an expensive mechanism’(6).

How successful was our dimmer? Does its existence today indicate that it stood the test of time or, as with so much country house technology, that investment in the Theatre wasn’t maintained in the 20th century?

Without further evidence, we can only speculate. Yet, regardless of its practical longevity, as an object at the vanguard of theatrical experimentation brought into Chatsworth only three years after the revolutionary introduction of electricity, this otherwise innocuous dimmer represents an extraordinary meeting of worlds at a very particular moment in time.

Learn more

Read/listen to other blogs in this series.

Behind the Scenes Tours

Our Behind the Scenes tours offer access to areas not normally open to visitors, including Chatsworth's Theatre. Find out more here.

Work, Play, Space and Identity at Chatsworth

Remaking the North Wing: Part One

Listen: Chatsworth's 'Theatre Royal'

Listen to researcher, Louise Calf, as she introduces us to Chatsworth's theatre and its role in entertaining a wide range of audiences, from royalty to pupils of a welsh all-girls boarding school.

History of Chatsworth

Learn about the Devonshires and discover how they shaped the history of the house, garden and collection that we see today.

Devonshire Collections

At Chatsworth, we care for one of the largest and most significant private collections in Britain, the Devonshire Collections.

Music from the archives

In the archive are pages of sheet music, recorded by different generations of the Devonshire family. Researcher and pianist, Elizabeth French, recently shared a selection of these pieces with Patrons of Chatsworth at an intimate evening performance.

References

(1) For an entertaining explanation and demonstration of a similar dimmer, watch this YouTube video.

(2) Marilyn Palmer and Ian West (2016) ‘Technology in the Country House’ Swindon: Historic England.

(3) p. 908 Bram Stoker (1911) ‘Irving and Stage Lighting’ The Nineteenth Century and After: A Monthly Review New York: Leonard Scott Publications Co. pp. 903-912. You can download a pdf copy of this article for free here.

(4) Palmer and West, p. 75

(5) Stoker, p. 908

(6) Ibid.

(7) Research suggests that the lighting in the Theatre was only updated in 2005.