We use platforms such as YouTube and Vimeo to display videos. These require the use of cookies, for which we need your consent. To watch this video, please click here to allow cookies.

Henry Cavendish (10 October 1731-24 February 1810) was the grandson of the 2nd Duke of Devonshire. Henry was born in Nice, France where his mother Lady Anne de Grey, fourth daughter of the Duke of Kent, was residing for her health.

The family returned to England before his younger brother Frederick was born in 1733. The same year, their mother died.

Henry was sent to school at Hackney Academy. He then attended St Peter’s College, Cambridge (now Peterhouse) from 1749-1753, leaving without a degree.

His father, Lord Charles, had purchased 13 Great Marlborough Street in London in 1738, setting up the stables as a laboratory and workshop. Henry lived there with his father until his father's death in 1783.

In 1758, Henry started attending Thursday meetings of the Royal Society’s Dining Club with Lord Charles. He was elected a member of that club and a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1760. He was elected to the council of the Royal Society thirty-four times and served on various committees, including those responsible for the organisation of the observation of Venus, another examining ways to secure powder stores against lightning, and those associated with care and upkeep of instruments at the Royal Society and the Royal Observatory.

During his lifetime, Henry published 16 papers in Philosophical Transactions, the journal of the Royal Society. His most prominent were his three papers on fictitious air ("Containing Experiments on Factitious Air", published 31 December 1766 Vol. 56), which earned him the Society’s Copley Medal, and "Experiments to Determine the Density of the Earth" (31 December 1798 Vol. 88). The latter details his most well-known experiment to calculate the mass of the earth, an experiment that still bears his name and earned him the posthumous moniker of “the Man who weighed the World”.

After his father's death, Henry inherited substantial property and wealth. He rented 11 Bedford Square (which he used as his library) and a house at Clapham Common (which he used as a laboratory and observatory).

He was said to be extremely shy, unwilling to talk to strangers, and kept his own routine of scientific meetings and experiments. Despite being an extremely wealthy man, he always dressed in the same outfit, wearing the same style of clothing for most of his life, calling his tailor to make a replacement set when one wore out.

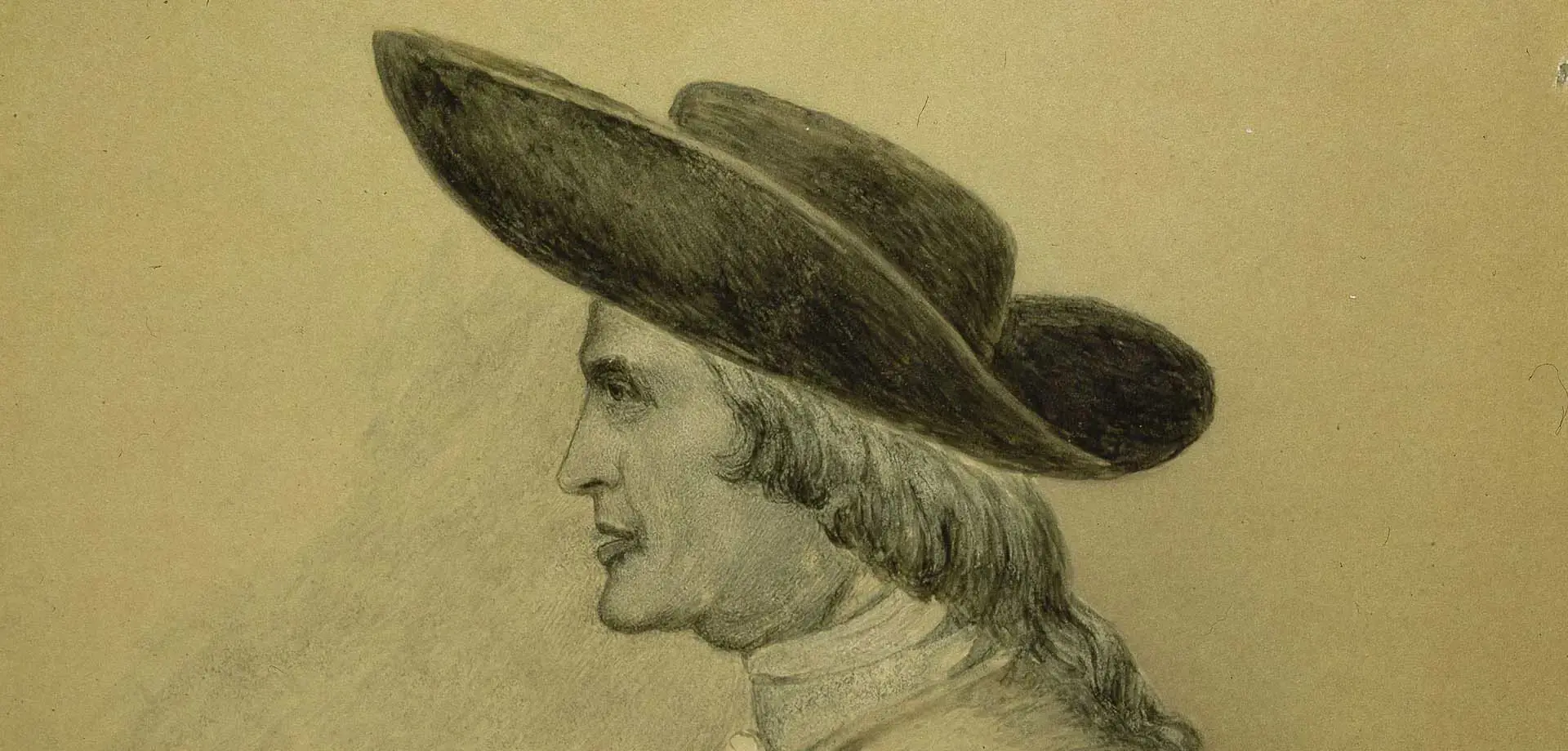

He refused to sit for a portrait so the only image of him created in his lifetime is a sketch made surreptitiously by an artist while they were dining at the Royal Society Club. He had a reputation for accuracy and precision, designing and re-developing experiments to avoid all potential for errors and repeating observations over decades.

Cavendish died aged 78 at Clapham Common and was buried, following a nine-day funeral procession, in the Devonshire family crypt in Derby Cathedral.

After his death, an examination of his papers revealed the scope, depth and genius of his scientific work.

Despite publishing only two papers relating to electricity in his lifetime, his manuscripts showed he had anticipated most discoveries about electricity that were to be “re-discovered” over the coming years including Coulumb’s and Ohm’s Laws.

In his works in chemistry, his papers on factitious airs could be said to represent the discovery of hydrogen and methane, as well as measuring the composition of oxygen in atmospheric air to a high level of accuracy. His experiments in 1781 led to his conclusion that water was a combination of oxygen and hydrogen.

Image credits:

Hon'ble Henry Cavendish natural philosopher lived here born 1731 died 1810 by Spudgun67 is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Henry Cavendish - 11 Bedford Square Bloomsbury London WC1B 3RF by Spudgun67 is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Henry Cavendish weighed the world at Clapham by Matt From London is licensed under CC BY 2.0.